The fabled Silk Road was the ancient trade routes linking China with the West. Through them, goods and ideas were exchanged between the two great civilizations of Ancient Rome and Ancient China. Originating in Xi’an, the 4,000-mile caravan tract followed the Great Wall of China to the northwest, continuing through the Takla Makan Desert, going up the mountains of the Pamir, and eventually reaching the territories along the eastern Mediterranean shores, like present-day Lebanon, Syria and Israel, among other countries. From there, merchandise was shipped across the Mediterranean Sea, with silk going westward, and wools, gold, and silver going east. Hundreds of years later, exchanges are still taking place on the Silk Road, but they are now of a deeply academic nature, and they are made between peoples of two completely different eras. Facilitating this new relationship are a variety of scholars and investigators, among them Joy Lidu Yi, associate professor of art history in the College of Communication, Architecture + The Arts (CARTA). Lidu Yi was recently selected as an FIU Top Scholar honoree for her research involving Buddhist art, architecture and archaeology in the rock-cut caves in and around the Silk Road.

Lidu Yi was born into a Chinese intellectual family and grew up on the campus where her mother worked. In Chinese tradition, painting has always held a prestigious status in society. Her parents’ wish was for her work to be related not only to Chinese painting, but also to calligraphy, a visual art form prized above all others in traditional China, a culture devoted to the power of the word. This was the initial direction she was taking with her studies until she started working on her M.A. and Ph.D. at the University of Toronto. One of her supervisors there was looking to train more students on Buddhist rock-cut cave art and architecture. His vision was that many scholars had already worked on paintings and calligraphy, while Buddhist cave art and architecture was a field in need of young academics to fill in the blanks and push forward scholarship.

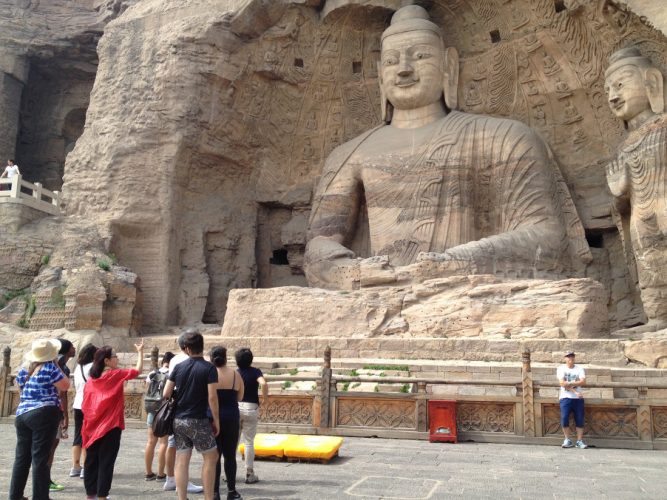

Since then, Lidu Yi has published a book featuring an ambitious investigation of a 5th-century rock-cut court Buddhist cave monastery, the Yungang Grottoes. The caves are a UNESCO World Heritage site and considered one of the greatest Buddhist monuments of all time.

“I have a sense of urgency to document and protect these World Heritage treasures,” says Lidu Yi when asked about her motivations. “They do not belong to any country, but to humankind. And perhaps this is the reason I work day and night without feeling tired or fearful while in the field.”

The volume was the first-ever comprehensive examination of the site in any Western language. Her inquiries about this impressive cave sanctuary were why and under what circumstances were the caves executed, who played significant roles at the various stages, and what was the construction dating sequence of the caves. She also delved into the question of how a religious space such as this functioned under the patronage of the court. New archeological discoveries in recent years provided invaluable hard evidence for her research, shedding significant new light on the architectural configurations of the location, the functions of different sections of this sacred sanctuary, and the monastic life which developed within it. For the first time, it was possible to have a better understanding of where the monks lived and translated sacred texts, as well as to fully comprehend the importance of the freestanding monasteries as components of the overall cave complex. The paperback printing of the book came out last month and Lidu Yi plans to expand the book into five volumes.

During her career, she has bumped into both, the elation over new findings and the despair over lost possibilities. “We have encountered very unpleasant moments,” she goes on to elaborate. “Some treasures we documented were completely looted after returning to caves several years later. Recently, we investigated some caves in Shanxi province in central plain China, but when we went back to work on them, all the images were chiseled away.”

“On the other hand, when we discovered an inscription with a date in a cave-chapel, the satisfaction cannot be expressed with words,” she gushes. “This happened in the Shifosi (stone Buddha) cave-chapel. When we first documented it over a decade ago, we didn’t see the inscription due to the darkness of the space, but it was discovered later.”

Her current research focuses on several Buddhist caves along the Silk Road. In addition, she is working with Chinese archeologists and scholars on relatively lesser-known cave-chapels in the Shanxi province.

“I feel it is my duty to train more young people in the field,” she says about her vocation as a professor. “Confucius promoted that teaching and learning develop hand in hand, so I believe that my research will inevitably have a profound impact on students’ learning.”

Lidu Yi is also interested in contemporary Chinese art and, whenever opportunity allows, she curates exhibitions of Chinese and Japanese artists. She has curated an exhibition featuring art by Japanese artist Koizumi Kishio (‘Remembering Tokyo’) at the Wolfsonian, and two others featuring Chinese artists Wang Qingsong (‘ADinfinitum’) and Xu Bing (‘Writing Between Heaven and Earth’) at The Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum.

“I think it is extremely important to make university museums a part of students’ life,” she remarks about her role as art curator. “Bringing in world-famous artists for exhibitions and to interact with students has a lifetime impact on them.”